Remodeling

2014 –

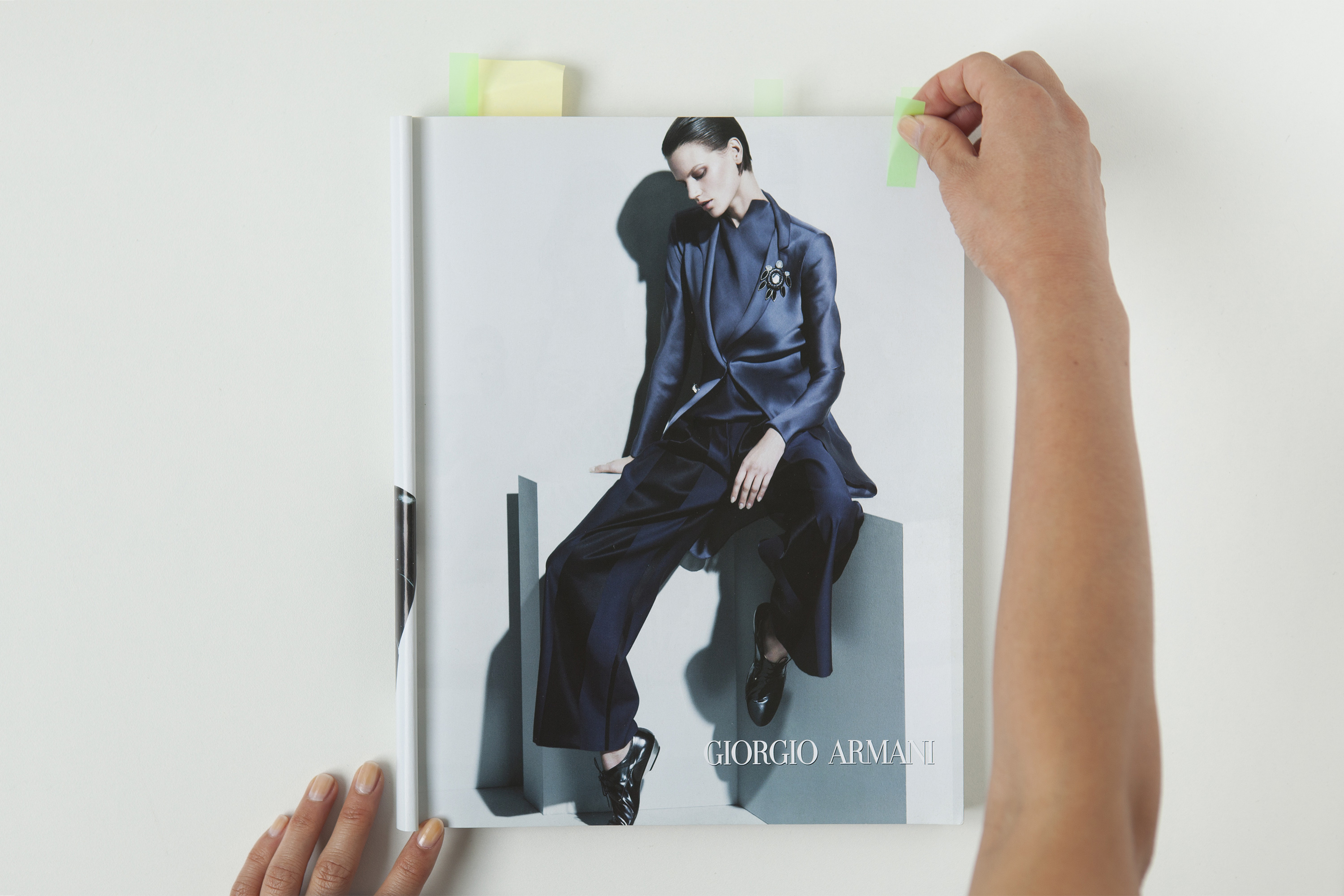

Remodeling is a project by Anneke Hymmen and Kumi Hiroi in collaboration with six writers. Hymmen and Hiroi started their project Remodeling by looking closely at the fashion industry through the images it produces. They were curious about the language of fashion the values they communicate.

They asked volunteers to describe in words a fashion advertisement that attracted their attention. The collected words became their working material. Without seeing the original images they began reconstructing their own, visual, interpretations of the descriptions at hand. They experimented using models (professional/not professional, young/old) with and without make-up, different lighting and location settings. The resulting 24 images show the diverse beauties in eclectic expression.

For the second part of the project six writers – Basje Boer, Jonathan Griffioen, Jetske van Heemstra, Shira Keller, David Pefko and Maartje Wortel – use these images as inspiration for short stories. With word count being their only limitation, they are free to drift away in their imagination and take us along for a ride into the worlds however real or fictional they may be.

Concept, Research, Development and Photo: Hymmen & Hiroi Text: Basje Boer, Jonathan Grifioen, Jetske van Heemstra, Shira Keller, David Pefko and Maartje Wortel

For the second part of the project six writers – Basje Boer, Jonathan Griffioen, Jetske van Heemstra, Shira Keller, David Pefko and Maartje Wortel – use these images as inspiration for short stories. With word count being their only limitation, they are free to drift away in their imagination and take us along for a ride into the worlds however real or fictional they may be.

Concept, Research, Development and Photo: Hymmen & Hiroi Text: Basje Boer, Jonathan Grifioen, Jetske van Heemstra, Shira Keller, David Pefko and Maartje Wortel

Viktor&Rolf – spice bomb, ELLE Nederland, june 2013, pg. 35, Photographer: Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matador, Model: Sean O’Pry

Gentlewoman spring and summer 2013, pg. 31, Photographer: Alasdair Mc Lellan, Model: Juliette Fazekas

H&M, VOGUE Nederland, december 2012, pg. 38, Photographer: Mikael Jansson, Model: Laetitia Casta

NO LEGS

When they arrive at the beach, it’s different than Line expected. This was supposed to be a cheerful climax that calmly settled everything back where it belonged. Line and her legs would be united again, and she and Wouter would be back together too. The sun should be out for that, at most surrounded by a few tiny clouds. Not wet mist. And definitely not crashing waves, tugging themselves upwards on fierce gusts of wind. “All right, Lin, let’s rock the boat,” Wouter says, reversing the car and backing rapidly and precisely into the slot. Line inhales deeply, smelling his fresh shampoo through a failed pine-scented car freshener. “OK, whatever,” she says, mainly replying to her own insecurities. “With or without?” Wouter asks, nodding towards the wheelchair on the back seat. “Without,” Line says; her tone sounds more challenging than she had planned. This is going well, she thinks, even as she forgets again what she’s actually here to do. “And with or without clothes?” Wouter asks cheerfully. “I’ll take off my dress on the beach, where there’s more room,” she replies.

The status quo for Line the last few weeks has been to be carried around. She had discovered to her surprise that unfolding a wheelchair generally took more time than she had (weren’t those things supposed to be user-friendly?), so when she was in a hurry, she was dependent on the strong backs around her. When she went to the systems therapist last month, her father carried her like a baby through the halls of the mental health institution, below the hideous lights. She felt safe cradled in his angular embrace. Once she had been set on a chair in the therapist’s office, she automatically let her strong father speak, reducing herself to a living reason for the talk. Exactly the right attitude to provoke the therapist. But the more he frowned at her, the softer her voice became. And the stronger his admonitions, the less clearly she understood them. In the end, it was her father who cried and her mother who asked the harder questions. Line concentrated on the view, a busy stretch of motorway.

Now she’s lying in Wouter’s arms, as he carries her down the stairs from the car park to the beach, curling up like a baby seems out of place. She tries to imitate a bridal scene, pressing her head against Wouter’s chest, her long brown hair blowing in her eyes. Wouter gives a mediocre performance in his role, sighing as he stumbles to the beach and dumps Line a bit too roughly on the sand, not far from the edge of the waves.

He had been enthusiastic when Line showed him the diagnostic report. “Like I thought,” he mumbled as he read it. The platonic version of their affair was starting to frustrate him, even though he had imposed it himself after the accident. Line was too beautiful not to touch, so her legs’ return would suit him perfectly. He had hoped for a conversion disorder, and had even come up with a verbal chain of events to explain it. Subconsciously, Line had talked herself into her own paralysis, and so convincingly that her legs had faithfully gone along with it. As he explained it, Wouter used so many complicated words that they turned everything into truth. He also had a theory about why the disorder had occurred. He articulated with excessive precision as he talked about her minimal sense of responsibility, the accident, her inability to communicate boundaries, their broken relationship. And his hairy hands made waving motions as he explained how the sea would help her. Necessity would make everything fall into place.

Without announcing his intentions, Wouter starts undressing Line. Her breasts are shrivelled with cold; her purple bra is loose in spots where it’s usually too tight. “Dipping, bobbing, diving, Alfred is always striving,”Wouter sings confidently, pulling her dress over her head. The sea is approaching rapidly, the surf line catching up to them. Line tries to find a good one-liner, but nothing comes to mind. She imagines she’s Wouter’s rag doll and only has to move along with his game. She nods her head woodenly up and down in time to his singing as Wouter takes off his own clothes.

The water is unpleasantly chilly. Leaning on her arms, Line props herself up. Wouter grabs her legs and pulls her several metres into the water. A salty wave slaps into her face and she feels around futilely with her hands, trying to find the ground to push herself up. Before she can panic, the current pushes her above the surface. “Now you’re going to do it, Lin,” Wouter cries; his voice is high and he lets go of her legs. The next wave crashes over her aggressively and the water rushes in through her nose. She uses her arms to push herself upwards. “Do you feel it yet?” Wouter shouts an encouragingly rhetorical question. As she coughs up water, Line tries to feel cold, water or necessity in her legs. Or at least a desire to swim to Wouter. Isn’t there something tingling in her lower left leg? And does she feel a nerve twitch in her left foot? Or is it the thought of a feeling? And what makes thought different from feeling? “Maybe,” she ventures, as the next wave washes over her.

Story by Jetske van Heemstra

Giorgio Armani, Gentlewoman spring and summer 2013, pg. 9, Photographer: Mert Alas & Marcus Pigott, Model: Saskia de Brauw